Extract insight from a set of flagged artefacts, and distil the information into usable threat intelligence.

Back to TryHackMe once again! This time I’ll be focusing on a Blue-Team heavy challenge room - Invite Only. I’ve been trying to target more threat-hunting and defensive challenges lately, so this should be fun!

As per the description of the room above it doesn’t seem like we’ll need to be doing any red-team activities, so this should be fairly straightforward!

Introduction

You are an SOC analyst on the SOC team at Managed Server Provider TrySecureMe. Today, you are supporting an L3 analyst in investigating flagged IPs, hashes, URLs, or domains as part of IR activities. One of the L1 analysts flagged two suspicious findings early in the morning and escalated them. Your task is to analyse these findings further and distil the information into usable threat intelligence.

We’re then given two IOCs (the findings that the L1 analyst flagged):

Flagged IP: 101[.]99[.]76[.]120 Flagged SHA256 hash: 5d0509f68a9b7c415a726be75a078180e3f02e59866f193b0a99eee8e39c874f

For what it’s worth I believe this is a real malicious IP, so it’s nice that this has been defanged for us. It makes it a little bit annoying when entering it into some tools (Like VirusTotal) but it’s better to be safe than sorry!

Here’s the rest of the message we get for this room:

We recently purchased a new threat intelligence search application called TryDetectThis2.0. You can use this application to gather information on the indicators above.

More on this application later. But for now let’s get to the questions!

What is the name of the file identified with the flagged SHA256 hash?

Once we load the machine up we can access the TryDetectThis2.0 application from the desktop. This is just a web-app that will take you to http://127.0.0.1:8000/.

The page we’re greeted by looks a good deal like VirusTotal. The page title suggests that this is an offline version of the tool that will just search through cached IOCs.

Alright - To answer the question.

This is pretty simple. We can just enter the SHA256 hash that we were given in the introduction (5d0509f68a9b7c415a726be75a078180e3f02e59866f193b0a99eee8e39c874f) into the search bar, Et voilà! We can see the name of the file associated with the file hash:

What is the file type associated with the flagged SHA256 hash?

We can see the answer to this question on the very same page. Right under the file name is the file type.

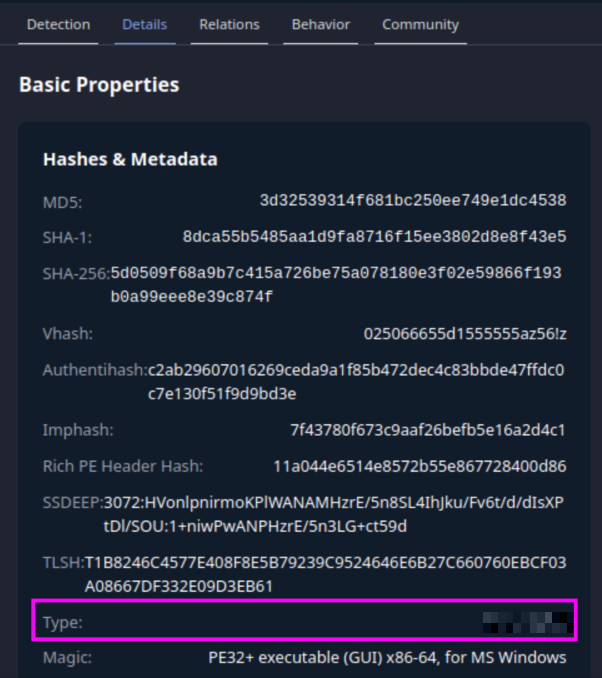

You can also see this answer if you go to the ‘Details’ tab of the file and scroll down to ‘Type’:

What are the execution parents of the flagged hash? List the names chronologically, using a comma as a separator. Note down the hashes for later use.

On the same page as the previous two questions we can check on the ‘Relations’ tab. You might need to scroll down a little but until you see the Execution Parents section.

For this answer you need to provide the file/friendly name. I got caught up on this initially, but you’re looking for the second name (Blurred out here):

What is the name of the file being dropped? Note down the hash value for later use.

If you scroll down a little bit more you can see the Dropped Files section with our answer. The filehash here is dd02c105809e4ca41a5489e585ba025eddb89a91703b73a566c9903e6406a08c, which we will keep in mind for a later question.

Research the second hash in question 3 and list the four malicious dropped files in the order they appear (from up to down), separated by commas.

Copy the filehash from the second file (with 24 detections) and search for that. From there we can check the ‘Relations’ tab and find the Dropped Files section.

The first three of the malicious files are immediately shown, but you’ll need to scroll down a little to find the forth one. Note that the answers are the only files that have any malicious detections on them.

Analyse the files related to the flagged IP. What is the malware family that links these files?

We can finally take a look at that defanged IP address that we were given: 101[.]99[.]76[.]120

It was here that I hit my first snag.

TryDetectThis2.0 is meant to be an offline version of VirusTotal. It worked great for the previous questions, but for this question I got quite confused.

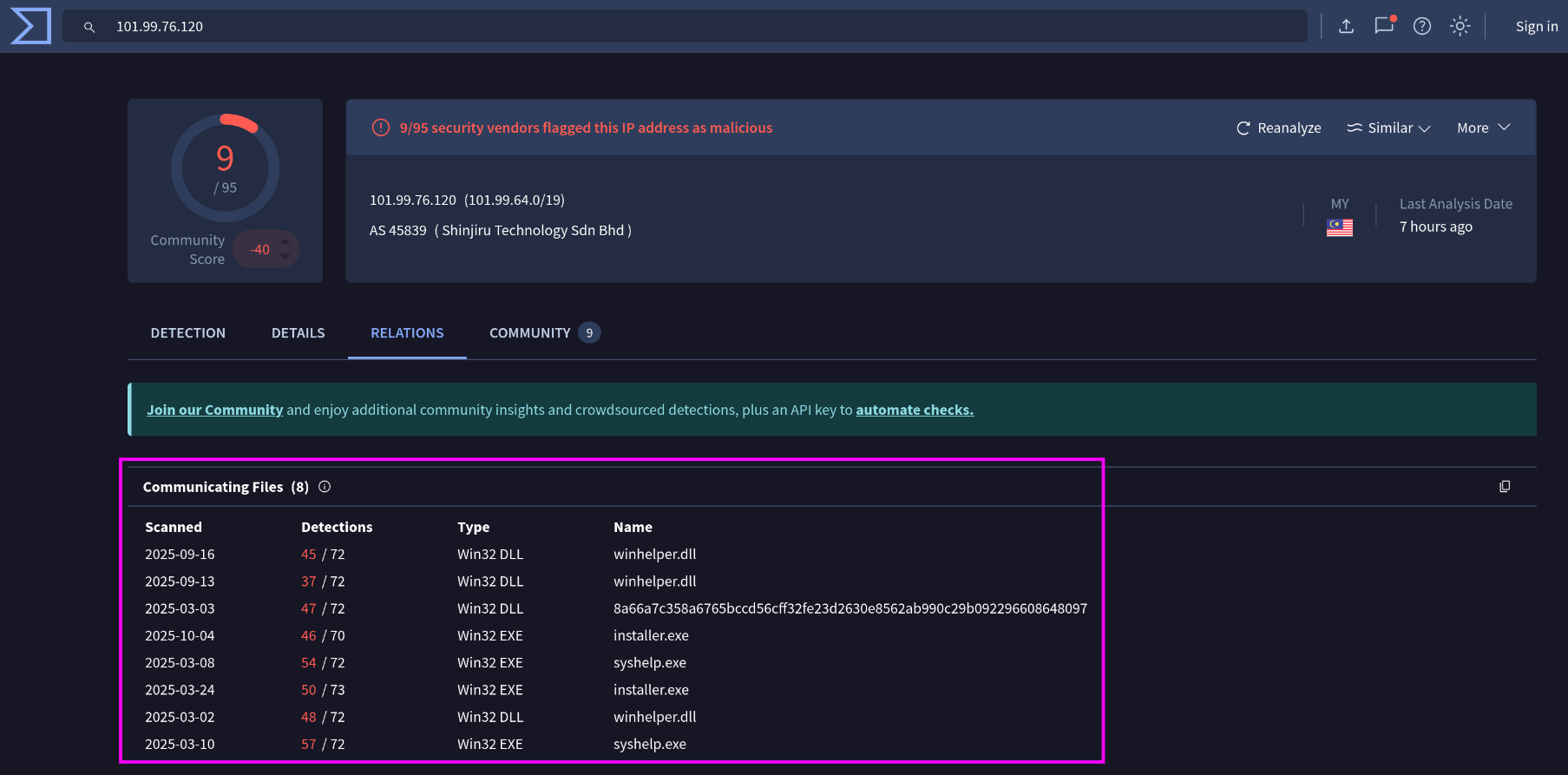

If we fang (Refang?) the IP address and search for it we can see that 12 vendors have detected this as malicious. That doesn’t get us closer to the answer but we know that we’re on the right path at least. I checked the ‘Relations’ tab and checked the ‘Communicating Files’ section. Each one of these hashes didn’t return anything though.

It took me a while to check all of the hashes just in case some of them were cached, but alas I was out of luck.

So what to do now?

I was tempted to check a Write-Up for this room to see if I had missed a step but instead found that there were no published write-ups shown on TryHackMe (Which is part of the reason why I’m writing this!). Ultimately I decided to use the real VirusTotal.

If we search VirusTotal for the IP address and go to the ‘Relations’ tab then we can see the proper ‘Communicating Files’ section.

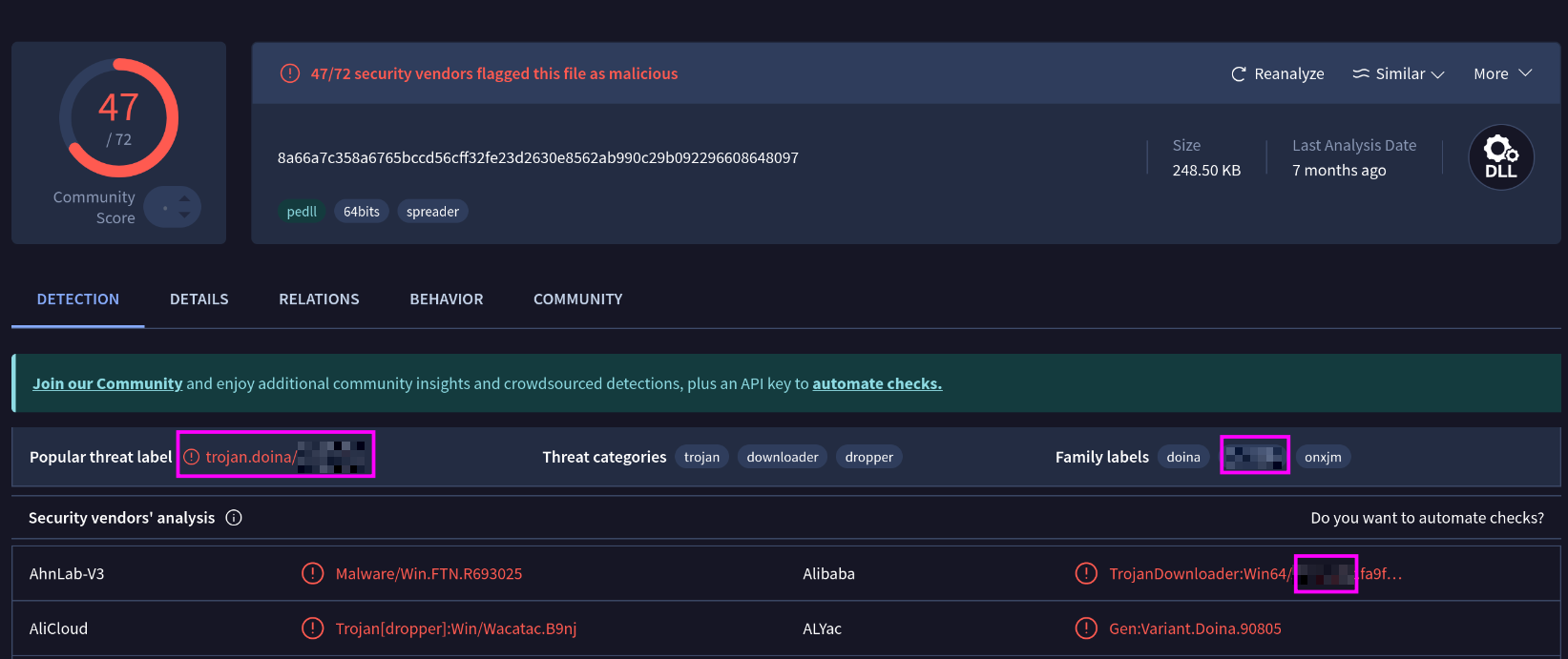

We can click on the names and investigate any of these files further. I decided to check on the file with the name that jumped out to me the most - 8a66a7c358a6765bccd56cff32fe23d2630e8562ab990c29b092296608648097

This is a file with 47 detections on it. There are a different malware families listed here, so we’ll need to check another one of those ‘Communicating Files’ to correlate it.

The malware family that these files relate to shouldn’t be too hard to spot, but just in case you’re getting stuck here’s a quick screenshot with the family blurred:

What is the title of the original report where these flagged indicators are mentioned? Use Google to find the report.

It’s at this point that you can turn off the TryHackMe virtual machine. We don’t actually need to use the TryDetectThis2.0 web-app anymore. Like the question suggests, we can use Google (Or whatever your preferred search engine is) to search for this report.

Google Dorking is a pretty important thing to be aware of. It’s useful in OSINT investigations and in threat intelligence/hunting. We know that there should be a report available that has listed the indicators, so let’s go searching for them!

My search query was pretty simple - “101[.]99[.]76[.]120”

This search gave me a report from the 16th of July from centripetal.ai about Discord invites being used in social engineering attacks. This report however mentions another report from Checkpoint. The Checkpoint report is from the 12th of June, and the title is the answer that we’re looking for.

The report is a pretty good read, and I recommend giving it a read outside of trying to find the correct answers. It comes down to Discord’s invite links, and being able to create Vanity invite links.

You’re probably familiar with Discord so I’m not going to explain it to you. When you join a Server you’ll often do it through an invite link. By default the invite link to a server is randomly generated, as mentioned in the Checkpoint report:

All Discord invite links follow the format:

https://discord.gg/{invite_code} https://discord.com/invite/{invite_code}

When an invite is generated you can select any custom expiration time up to 7 days. Invite codes are randomly generated and typically contain 7 or 8 characters, combining uppercase letters, lowercase letters, and numbers. Permanent invite codes also exist and contain 10 characters & numbers.

So what’s the vulnerability?

If a server has a Level 3 boost (You can just pay to have perks like emojis and the like) then you can create a Vanity URL. Usually these will be done to add the name of a company or community to the url, like https://discord.gg/Legitcode. The exploit for this comes in that there aren’t any restrictions on changing your Vanity URL to an expired invite code.

For example, let’s say that a streamer has a Discord server. They have a permanent invite link linked on their Twitch page. Maybe they don’t set the expiry properly and it lapses after 7 days, but the invite code is still linked on their Twitch page. From here and Attacker can create a Vanity URL that reuses the previous invite code they are using on their Twitch page. Now anyone who clicks on that link is redirected to the attacker-owned page. Make sense?

The report shows how this can lead from a ’trusted link’ leading to a Malicious Discord Server where the ‘Verification’ process has you going through a ClickFix attack.

With all that covered, let’s complete this room!

Which tool did the attackers use to steal cookies from the Google Chrome browser?

Scroll down through the report until you get to the header Campaign Evolution and Addition of New Modules. Here the report details how attackers have found a way around Chrome’s Application-Bound Encryption, which is a security feature that is meant to prevent cookies from being extracted. The name of the tool is on the third paragraph under the heading.

Which phishing technique did the attackers use? Use the report to answer the question.

I mentioned the technique previously. I’ve seen some discussion around whether this is just a social engineering technique or if it’s an actual attack by itself, but it’s a smart a way to get users to run malicious code on their own device. If you’re stuck on this, check the Key Takeaways heading right at the top of the report.

What is the name of the platform that was used to redirect a user to malicious servers?

This should be pretty simple to answer. The platform/application that allows you to create Vanity URLs is another hint in case you’re lost.

Conclusion

Once again another fun room from TryHackMe. Although TryDetectThis2.0 is suggested, you don’t really use it past the first few questions. I would have preferred if the room just asked you to use VirusTotal instead (Although this negates the use of the AttackBox entirely). Getting hands on experience with Threat Hunting tools like VirusTotal is important if you’re getting into the blue-team side of things, I’ve used it almost daily in my job.

I mentioned previously how nice the CheckPoint report was. It detailed an attack I had never heard of, and I’ve been using Discord for almost 10 years now. Interestingly though Discord have not patched this. As per the report:

Discord took swift action to disable the malicious bot used in this campaign, which helps disrupt the current infection chain. However, the broader risk, that attackers could create new bots or adopt alternate delivery methods that leverage the same core techniques, still remains.

It’s great that they removed the ‘Verification’ bot, but the underlying issue still remains, so be careful!